A correct translation of the title of Ivan Pavlov’s magnum opus is not Conditioned Reflexes. Pavlov studied unconditioned reflexes. The title of his book is Conditional Reflexes. In Russian, the word for conditioned and conditional is the same. You can only know which meaning is correct if you put the word in context. The English translator didn’t know the context – just like modern behavioral scientists. If you think this is a small thing, read on.

Category Archives: Training

Never-never, say it-say it, twice-twice: Commands and Signals.

Commands vs. Cues and Signals

Originally printed in Front & Finish by Gary Wilkes

Almost every hobby, discipline or science has a way of adopting words to suit it’s own purpose. Often, these special terms have older and more basic meanings in general conversation. For instance, in the context of obedience regulations, a command is a verbal cue and a signal is a visual cue. In order to fully discuss how dogs learn to respond to specific cues, we need to use these words in their more general meanings. So, for the purpose of this column we will stick to Webster’s definitions. Continue reading

The Legend of the Trained Monkeys

Once upon a time there was a family circus that was down on its luck. They had a string of shows that didn’t draw big crowds and couldn’t make payroll. Their “roadies” quit and left them sitting near a railroad siding in Kansas. Their circus cars, animals, wagons and tents were on a rail siding with no hopes, prospects of future. The family was about to sell off the whole shebang when they got a telegram from Canada. A group in Toronto wanted them to come and perform their show. They would even send an engine down to haul the circus train north. The family realized they wouldn’t be able to set up the tent when they got there but figured it was better to take the money and try to find a way to insure that the show would go on. Continue reading

George Hickox: Master Trainer

Eddie (a girl-dog) all grown up and going for a pheasant.

One of the most enjoyable afternoons I’ve ever spent in my life was in a chopped down cornfield near Hugoton, Kansas. George Hickox invited me to a week of pheasant hunting and I was also there to help out some of his clients with their dogs. That first afternoon, George and I went out to look at two of his dogs that were for sale. For four hours we put the dogs through their paces, flushed some pheasants and simply commented on what we were seeing. To hear the cogent comments of a master trainer is priceless. George is a master. I am honored that he thinks I am, too. We have different perspectives and different experience, but we both love and know dogs. If you are jealous of my day tramping across cut-down corn fields and wading through hip-high brush with George, you’ve got the right stuff. (Photo from Sand Wells Outdoors. Photo By Bill Buckley) Continue reading

Variability – The Key to Learning

Here’s a conundrum for you. Scientists claim they have created something called “Learning Theory” that explains, of course, learning. There is a singular problem with this claim. The research used to develop this perspective doesn’t include a decent examination of behavioral variability. In case you are getting the hint already, learning is necessarily a variation on an existing repertoire or the creation of completely new behaviors. The existing repertoire allows you to “repeat” functional behaviors. Learning requires that you temporarily abandon “repeat” and instead, do “different.” If they want to have a theory of learning, how come they don’t study “do different?” That would require a completely different research methodology. I know that because behavioral scientists have tried to study variability in an operant chamber without actually changing their methodology – ironically they are themselves incapable of “doing different” to study “do different.” Here’s what they did do – a repeat of their existing repertoire of having an animal repeat itself endlessly with a wrinkle that barely passes as a variation.

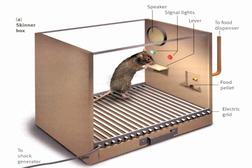

Behavior analysts studying variability took a standard “Skinner Box” and added another lever. Then they reinforced rats for pressing combinations of lever presses – usually in series of four. Left-Left-Right-Right (LLRR) would be an example of a four-press set. To create variability, they connected a specific signal to indicate that the pre-set pattern would be reinforced. Then they added a second light. If second light was on, the original pattern (LLRL) caused the machine to time-out. Any “repeat” behavior caused time-outs while new variations brought reinforcement. (LRLR, LRRR, RLLL, RLRL, etc.) Bril liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer) Continue reading

liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer) Continue reading