Here’s a conundrum for you. Scientists claim they have created something called “Learning Theory” that explains, of course, learning. There is a singular problem with this claim. The research used to develop this perspective doesn’t include a decent examination of behavioral variability. In case you are getting the hint already, learning is necessarily a variation on an existing repertoire or the creation of completely new behaviors. The existing repertoire allows you to “repeat” functional behaviors. Learning requires that you temporarily abandon “repeat” and instead, do “different.” If they want to have a theory of learning, how come they don’t study “do different?” That would require a completely different research methodology. I know that because behavioral scientists have tried to study variability in an operant chamber without actually changing their methodology – ironically they are themselves incapable of “doing different” to study “do different.” Here’s what they did do – a repeat of their existing repertoire of having an animal repeat itself endlessly with a wrinkle that barely passes as a variation.

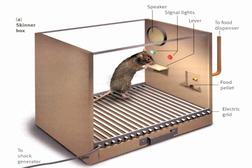

Behavior analysts studying variability took a standard “Skinner Box” and added another lever. Then they reinforced rats for pressing combinations of lever presses – usually in series of four. Left-Left-Right-Right (LLRR) would be an example of a four-press set. To create variability, they connected a specific signal to indicate that the pre-set pattern would be reinforced. Then they added a second light. If second light was on, the original pattern (LLRL) caused the machine to time-out. Any “repeat” behavior caused time-outs while new variations brought reinforcement. (LRLR, LRRR, RLLL, RLRL, etc.) Bril liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer)

liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer)

The fly in the ointment is this – repeating the same behavior in different patterns is like playing cards. It does not represent true variability. Real variability occurs constantly in animals that have instinctive repertoires and innate but conditional sensitivities to external events. Animals in operant chambers have a single behavior. No information is recorded about the way they press the lever. Too bad. To prove that this is true I offer you a tale from Ogden R. Lindsley, PhD. This is Og and me at a seminar I gave in Wichita, KS. You can read about it at http://www.clickandtreat.com/html/ff019.htm If you ever consider “science” as being applicable to your knowledge of behavior it would benefit you to go to this link and drink in the life of Ogden R. Lindsley – http://precisionteaching.pbworks.com/w/page/18241059/Ogden%20Lindsley%20%281922-2004%29#HarvardBehaviorResearchLabandtheJournaloftheExperimentalAnalysisofBehaviorJEAB

The fly in the ointment is this – repeating the same behavior in different patterns is like playing cards. It does not represent true variability. Real variability occurs constantly in animals that have instinctive repertoires and innate but conditional sensitivities to external events. Animals in operant chambers have a single behavior. No information is recorded about the way they press the lever. Too bad. To prove that this is true I offer you a tale from Ogden R. Lindsley, PhD. This is Og and me at a seminar I gave in Wichita, KS. You can read about it at http://www.clickandtreat.com/html/ff019.htm If you ever consider “science” as being applicable to your knowledge of behavior it would benefit you to go to this link and drink in the life of Ogden R. Lindsley – http://precisionteaching.pbworks.com/w/page/18241059/Ogden%20Lindsley%20%281922-2004%29#HarvardBehaviorResearchLabandtheJournaloftheExperimentalAnalysisofBehaviorJEAB

Og was B.F. Skinner’s teacher’s assistant and later research colleague at Harvard. He went on to become a great behaviorist. To my reckoning, the greatest. I was honored to have him call me friend for the last 12 years of his life. We talked a great deal about many topics. According to Og, he and Skinner had a project that used Beagles to sniff the urine of women to determine if the women were pregnant. They used an old refrigerator turned flat as their operant chamber to keep extraneous scents away from the beagles. They had a lever mounted in the box, just like in rat chambers and the experiment appeared to be working perfectly with one small hitch. When the beagles figured out what they were looking for, they didn’t just press the lever. They banged on it with alternating feet and bit the lever in a wild assertion of their success. Skinner didn’t like that. He instructed Og to make a metal sleeve that would only allow the dogs to put a single leg forward to press the lever. It didn’t work, either. The dogs almost dislocated their shoulders trying to continue to use both legs and their mouths – the same behavior that many breeds of dogs use when trying to dig up burrowing animals. An instinctively hard-wired set of behaviors was ruining the isolation of the operant chamber. Beagles as a breed are incredibly variable. When they lose a scent, they wander around in tight, erratic circles to find the scent again. None of this information was contained in Skinner’s findings. He didn’t want it. Variability wasn’t important to him. He wanted “clean” data. I’ll tell you about the time Og set up a feeder station for a pigeon in the hallway outside the Psych Office at Harvard sometime. “Clean” data comes from expert observation, not austere surroundings. Skinner never figured that out – but he never actually trained animals, either. Og did figure it out and he did train animals in the real world. My favorite quote from him is this – “You must always remember that the box is not there to keep the animal in, it is there to keep the world out.” Truer words were never spoken. When you hear the words “learning theory” just remember Og’s advice.

The point is that to understand learning one must understand natural and learned variability. It is the foundational behavior that leads to all learning. i.e. If you cannot “do different” you cannot learn. If you cannot create variability in a dog or other animal you cannot teach them new things. If you want to see what I am talking about, try this little exercise. http://www.clickandtreat.com/Clicker_Training/GG/GG001/GG002/GG003/ff007.htm