Once upon a time there was a family circus that was down on its luck. They had a string of shows that didn’t draw big crowds and couldn’t make payroll. Their “roadies” quit and left them sitting near a railroad siding in Kansas. Their circus cars, animals, wagons and tents were on a rail siding with no hopes, prospects of future. The family was about to sell off the whole shebang when they got a telegram from Canada. A group in Toronto wanted them to come and perform their show. They would even send an engine down to haul the circus train north. The family realized they wouldn’t be able to set up the tent when they got there but figured it was better to take the money and try to find a way to insure that the show would go on. Continue reading

Category Archives: Behavior Modification and Training

DRO, DRA – silly concepts and dead dogs.

Behavior analysts have a language of their own. This makes sense as their language is designed to describe what happens in a tiny little box where rats press levers and pigeons peck keys. Most of it doesn’t make sense. All of it demonstrates a bias that ignores reality. Perhaps the weakest concept to come from behavior analysis is the idea that positive reinforcement can remove inappropriate or unacceptable behavior. According to them, all you have to do is create a situation where you apply “differential reinforcement.” The differential part is that one behavior is reinforced and other behaviors are not. Supposedly this will cause the unreinforced behavior to go away. For instance, many modern dog trainers and behaviorists suggest that you can stop a dog from rushing the front door by teaching it to lie down for treats. The two jargon terms for this process are differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) or differential reinforcement of alternate behavior. (DRA) At best, these two terms reveal an unscientific bias that permeates behavior analysis. The bias is in favor of “positive” methods and opposed to “negative” methods. Continue reading

Variability – The Key to Learning

Here’s a conundrum for you. Scientists claim they have created something called “Learning Theory” that explains, of course, learning. There is a singular problem with this claim. The research used to develop this perspective doesn’t include a decent examination of behavioral variability. In case you are getting the hint already, learning is necessarily a variation on an existing repertoire or the creation of completely new behaviors. The existing repertoire allows you to “repeat” functional behaviors. Learning requires that you temporarily abandon “repeat” and instead, do “different.” If they want to have a theory of learning, how come they don’t study “do different?” That would require a completely different research methodology. I know that because behavioral scientists have tried to study variability in an operant chamber without actually changing their methodology – ironically they are themselves incapable of “doing different” to study “do different.” Here’s what they did do – a repeat of their existing repertoire of having an animal repeat itself endlessly with a wrinkle that barely passes as a variation.

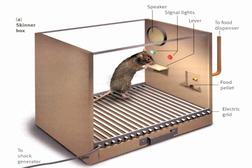

Behavior analysts studying variability took a standard “Skinner Box” and added another lever. Then they reinforced rats for pressing combinations of lever presses – usually in series of four. Left-Left-Right-Right (LLRR) would be an example of a four-press set. To create variability, they connected a specific signal to indicate that the pre-set pattern would be reinforced. Then they added a second light. If second light was on, the original pattern (LLRL) caused the machine to time-out. Any “repeat” behavior caused time-outs while new variations brought reinforcement. (LRLR, LRRR, RLLL, RLRL, etc.) Bril liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer) Continue reading

liant. With this set up you can do all kinds of analysis of variability of how often a rat does the same behavior. You can infer all kinds of things and then extrapolate your findings to publish peer-reviewed papers. Just don’t do it too much. Studies regarding variability represent a tiny fraction of actual behavior analytic research. (If you wish to see the best of the best on this topic, look up Allen Neuringer) Continue reading

Dusty the No Longer Nasty Cocker

This is a letter I received from a woman who brought her aggressive Cocker to a seminar. This kind of aggression is typical of Cocker Spaniels – a bit moody and serious when it uncorks. I add this to the blog because it describes the typical result of using my methods and I didn’t write it or edit it. It is not meant to be a testimonial, but an account of a process that saved this dog’s life…Gary Wilkes

Dear Gary,

I hope you remember me and Dusty from the seminar you conducted in Vernal, Utah, last September. Dusty was the beautiful, angelic-looking Cocker Spaniel with the long eye lashes. I wanted to give you an update on his progress and thank you for all of your help. Dusty’s behavior has improved so much that it’s unbelievable. When we got back to Salt Lake after the seminar, Dusty was in a very compliant mood. But the first time I tried to enter the TV room, Dusty gave me “the look,” so I yelled “No!” and let the bonker fly. It worked! I had to give him one refresher bonk a few days later, but I can now walk into any room, frontwards, make eye contact with him and he doesn’t even growl, let alone attack me. Continue reading

Bad Language and Modern Dog Training:

Using language precisely is not a hallmark of modern training and behavior. Consider that the word “positive” is used to mean beneficial and “negative” is used to mean harmful, abusive and cruel. This is done both when speaking to the general public (something doctors never do) and within the profession, where a higher standard of language should be upheld. For instance, the word punishment is regularly used as a pejorative that implies abuse, even though the scientific definition does not imply anything other than something that causes behavior to decline or stop. EG: “Punishment-based-trainer” is intended as an insult, not a neutral statement about a training philosophy. It’s not accurate, either. A leash and collar is a device that applies positive punishment and negative reinforcement – both considered “negatives” by all-positive trainers. Obviously, if you use a leash, you are by definition a punishment-based trainer. Additionally, if you use a leash to stop a dog from lunging, you are using “positive” punishment. We all know that this would be called “negative” by the same people who claim to be all-positive. The language (and the concepts behind the words) are used almost exclusively in a rhetorical manner to promote an ideology that is incompatible with a full reading of the scientific literature. Meaning it is not just imprecise, it is incorrect. Continue reading