In the world of veterinary medicine, shelter management, police enforcement of civil laws and modern behavioral treatment of the mentally disabled, restraint is an acceptable response to violence. If a dog, cat or human attempts to initiate violence they will be subdued. The problem is that such restraint does not prevent the violence from occurring in the future. In the case of mentally disabled animals and humans, it may lead to a perpetual nightmare of attack and defense that never goes away. Imagine how a person incapable of controlling their behavior internally responds to being jumped by thugs on a daily basis, ad infinitum. My question is, why is such restraint acceptable? It is risky, reactive, chaotic and dangerous. It triggers fear (and often escalates the violence) and can cause pain and damage, no matter how careful the restrainer may be. The literature of behavior analysis and common objective observation of nature suggests that contingent punishment can stop or dramatically reduce such violence. That is almost never mentioned and is opposed, routinely. That generates some interesting questions.

Here’s my second question. If a person breaks their own nose repeatedly, why would it be unacceptable to break their nose intentionally, if it could stop the behavior for the future? If the person is not aroused when you break their nose, it may well suppress the behavior in the future. This is not hyperbole or a hypothetical. The person breaks their own nose on a regular basis. The doctor at an ER may have to break the nose again to correct a breathing problem caused by restraint. This will have no effect in stopping the behavior but is perfectly acceptable, even if it is done over and over again. So, the ER doctor can break the victims nose in cold blood, after the fact with no thought to a recurrence. The doctor is not required to wonder why the same patient keeps breaking his nose. The behavioral therapist is ethically bound to try to stop the behavior. They rarely uphold their responsibility. Instead, they suggest better protective gear.

It should be pointed out that when a person becomes aggressively aroused, they become insensate to pain. That is why violent restraint doesn’t stop their behavior in the future. It is not perceived as an aversive event to the point it would suppress the initiation of violence. Additionally, as restraint is reactive, there is no marker that delineates which behavior is responsible for the violent conclusion. Humans have used the words, “NO” and “Stop” for millennia to attempt to make punishment contingent. No such marker is used in restraint. In effect, the restraint is simply non-contingent nastiness, as perceived by the recipient. We know that.

Below is a quote from a BCBA in private practice. It is perfectly anecdotal, but it is not unique. I have spoken to many practitioners who have the same problems. That is because I have on several occasions spoken at ABAI and regional ABA conferences on the topic of punishment. They are always well attended. They always draw practitioners who admit to using punishment but have never been taught to use it effectively. Anyone who wishes to find out how common this is would simply have to talk to behavior therapists in the bar at any ABAI conference. That’s where I first heard it. The ratio of presentations at the 2008 CalABA conference on some aspect of reinforcement vs. punishment was 143:1. At the 2009 ABAI conference it was 150:1. One cannot learn that which is not taught. So, they reinvent the wheel in secret. It must be done in secret because their mentors and controllers have made it impossible to discuss the topic or apply punishment that could stop nose-breaking.

“”Here in my current position, I often struggle with years and years of ‘reinforcement’ procedures that still have my students breaking their own noses and requiring 2-person holds – often on a daily basis, and an absolute resistance to even discussing the possibility of using a punishment procedure.”

According to the literature of behavior analysis, reinforcement increases behavior and punishment reduces or stops it. There are numerous peer-reviewed papers that indicate conclusions using the phrase “complete suppression.” Why would one allow their loved one to be under the care of someone who knows this is possible but opposes it’s use?

From the ABAI website – it may still be there, but was there in the public area for about ten years.

“Throughout his career, Skinner opposed the use of all forms of punishment; he advocated positive ways of changing behavior.”

If this is true then we understand two things. First, Skinner opposed the use of a behavioral effect proven by his own scientific discipline to be more effective than “positive” methods at stopping behavior. Second, the current resistance to objectively studying punishment is the result of ideological devotion to people and their ideas rather than to veritas – truth for truth’s sake.

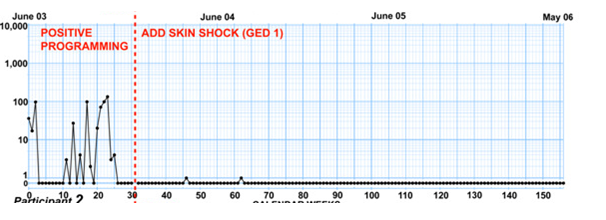

This is from a cased study by JRC – a clinic where they use punishment to stop things. The chart is from an adult suffering from self-injurious behavior akin to nose-breaking. It means that there is a single behavior that does not respond to “positive programming” and a single individual who benefitted from punishing the behavior. Now you know that punishment can be an effective way to stop such behavior.

As behavioral therapists you must gain informed consent before you can treat someone. Informed consent cannot be given unless the therapist offers information about treatment known to be effective – all treatments known to be effective. EG: A chiropractor may not withhold information about surgery that could permanently fix an orthopedic condition and claim they gained informed consent. An ABA practitioner may not gain informed consent while presenting Skinner’s preference for “positive” ways of changing behavior. They must also show or explain about the JRC chart as a potential treatment. If this information is withheld, it leads inexorably to withholding treatment known to be effective. That means the nose-breaking and violent restraint will continue, unabated. The decision isn’t up to the therapist. If the guardian choses to block the use of punishment, so be it. Continuing to provide treatment known ‘not to be effective’ is another story. That puts the behavioral therapist in the position of blocking effective treatment.

In 2007, two years before I presented a workshop on punishment at the ABAI conference, Charles Catania wrote this about JEAB.

Research on human behavior therefore does not seem threatened, but a different topic seems to be in jeopardy. The analysis of aversive control has almost vanished from JEAB. The sole exception in Volume 87 is an article on aversive control with humans, on the effectiveness of restraint as a punisher of stereotyped behavior in autism (Doughty, Anderson, Doughty, Williams, & Saunders, 2007). Has the conduct and publication of research on punishment and escape and avoidance and conditioned suppression and related phenomena been punished? At the least, it has not been much reinforced. It is probably relevant that the links in the initiating chains for such research (Gollub, 1977) have become extended with the interposition of Institutional Review Boards and the corollary requirement that experimental protocols be specified in advance. Could Sidman’s (1958a) tour de force have been conducted in a contemporary laboratory? (Bold, mine. GW)

Have we learned enough about aversive-control phenomena in the past half-century that we do not need to study them any more? How much do we know about conditioned punishers as they may operate in extended chains and other complex schedules (e.g., Silverman, 1971), and can we afford the assumption that differences between reinforcement and punishment are essentially matters of changes in sign? In a world so filled with aversive events that enter into various contingencies with behavior (Perone, 2003), can we entertain any extensions of our applications without continuing or expanding our experimental analyses of these phenomena?

When I post things on the ABA Facebook page I get illogical rebuttals and resistance to any mention of aversive control. They range from “no, we don’t do that” to “It’s inhumane. (Travis Thompson) to “society won’t let us do it.” When I reference peer-reviewed evidence from journals and scholarly texts it is dismissed as argumentative or disruptive behavior and the attempt is to marginalize my comments. There’s a problem. It’s not me. It’s Catania, Israel, Lindsley, Azrin, Ulrich, Van Houten, Axerod, Apsche and a host of other behavior analysts who worked to tell the truth. The nose-breakers are waiting for someone to speak about aversive control objectively based on the evidence of science and reality. Is Catania correct? Has research, discussion and the development of practical applications been punished? The statistics say yes. If he read my anecdote above, would he be surprised that this punishment of the discussion and practice of punishment as valid therapy carries from the highest levels of the discipline all the way down to those who must clean up the blood from broken noses? Ask him. He’s in the membership list on the ABAI website.

The natural world says “yes” or “no” pretty effectively via consequences. Choosing to ignore that fact by refusing to study or utilize even minimal punishment procedures during the treatment of severe problem behavior typically leads to the use of far more restrictive and dangerous “procedures” down the road. Even saying “no” to children with autism is still a “no-no” in many circles. Why would you withhold half of the evolutionary equation from individuals who struggle to understand how the world works due to the fact that their neurology is a mismatch from birth to the natural world? It’s irresponsible and cruel and not at all befitting of a culture that says it understands enough about human behavior to step in and take charge of these children’s lives while at the same time choosing to ignore a combination of “tools” that might provide a livable future for all involved. Mother nature will extract a heavy price at some point, she always does. Why should she care if you don’t?

Robert, I especially like your statement – “Why would you withhold half of the evolutionary equation from individuals who struggle to understand how the world works due to the fact that their neurology is a mismatch from birth to the natural world?” True elegance in speech is a beautiful thing. Major kudos for so succinctly wrapping up the topic.