If you have never seen the original movie, The Karate Kid, it’s a good idea to find it, watch it and comprehend the most important part. A teen wants to learn how to protect himself from bullies. The gardener at his apartment complex is a very quiet man named Mr. Miyagi, who just happens to be a karate master. During the first experiences learning Karate, the kid is totally frustrated. Instead of learning how to punch and kick, Mr. Miyagi tells him to wash

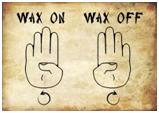

If you have never seen the original movie, The Karate Kid, it’s a good idea to find it, watch it and comprehend the most important part. A teen wants to learn how to protect himself from bullies. The gardener at his apartment complex is a very quiet man named Mr. Miyagi, who just happens to be a karate master. During the first experiences learning Karate, the kid is totally frustrated. Instead of learning how to punch and kick, Mr. Miyagi tells him to wash  and wax his old truck – in a very specific fashion. Wax On is one movement and Wax Off is a different movement. Finally, the kid rebels and questions the advice. Miyagi commands, “Wax On!” and throws a punch – the kid makes a movement upward with his arm, Wax On, – and blocks the punch. Then Miyagi comamnds, Wax Off! – and the kid’s arm movement blocks another punch. Then Miyagi sighs and questions the

and wax his old truck – in a very specific fashion. Wax On is one movement and Wax Off is a different movement. Finally, the kid rebels and questions the advice. Miyagi commands, “Wax On!” and throws a punch – the kid makes a movement upward with his arm, Wax On, – and blocks the punch. Then Miyagi comamnds, Wax Off! – and the kid’s arm movement blocks another punch. Then Miyagi sighs and questions the  wisdom of teaching someone who does not know how to be a student. So, in the spirit of Mr. Miyagi I am going to teach you something that will help you understand dog training but will initially not seem connected. It will try your patience and most likely, you won’t do it. The vast majority of people don’t. Sigh. So, if you are up for learning something that can’t be learned through any other way that directly affects your ability as a dog trainer, here goes.

wisdom of teaching someone who does not know how to be a student. So, in the spirit of Mr. Miyagi I am going to teach you something that will help you understand dog training but will initially not seem connected. It will try your patience and most likely, you won’t do it. The vast majority of people don’t. Sigh. So, if you are up for learning something that can’t be learned through any other way that directly affects your ability as a dog trainer, here goes.

Writing with your “off” hand: Tools: Writing paper and pen.

Step 1. Pick up the pen with the hand that you don’t normally use for writing. Don’t pick it up the way you do a writing instrument. Just pick it up as if it was a Popsicle stick or a thermometer. Now move it around in your hand. Try making it rotate between your fingers so that it spins like a baton twirler’s baton. If you drop it, pick it up and try again. Now place the pen back on the paper. Do this for about 3 minutes. If you feel more comfortable, use a kitchen timer or do it during the commercials between segments of any television show. Feel free to put the pen down and pick it up again several times. At the end of about 3 minutes, put the pen down and take a break.

Step 2. Pick the pen up the way you would any normal pen. Now try to print the word CAT. That is the type of word that we all first learned to write. As you write the letters, try to sense the feeling of discomfort that goes along with doing something that would feel perfectly comfortable if you were allowed to do it your way. Remember this step, we are going to return to the importance of it later.

Step 3. Let’s get a little tougher and try to write the word cat in cursive writing. If you notice, trying to write with each letter flowing into the other is far more difficult than printing individual letters. (It’s harder to read, too.) If you really want to stretch your patience and learn this exercise correctly, try to write the same words that you see in cursive script, above. If you do, you will start to get frustrated at about “trying.”

Step 4. Unless you are really persistent, you are probably getting a little tired of this exercise that appears to have nothing to do with your express goal – dog training. Since you can’t see a logical connection between the task and the goal, any difficulty you experience will compound your resistance to learning anything else, or trusting that I know what I am doing as your instructor. So, we will make the task a tiny bit easier. For this step, try writing your signature slowly and as closely to your normal signature as possible. Write your name five times and then put the pen back on the table.

Step 5. Pick up the pen with the hand that you normally use to write. Repeat each of the exercises above with your dominant hand. Pay special attention to how easy it is to whip off the letters as if you were tying your shoes or brushing your teeth. There is no uncomfortable feeling as you blast through the task. Mission accomplished. Place the pen back on the table and take a short break before reading any longer.

What’s the point?

There are several important points infused into this little project. First, you get to know viscerally how your dog feels when it is trying to learn something new or something that is a simple modification of something it already knows. You have a clear idea of what’s going on but the dog is as clueless as Ralph Maccio complaining to Mr. Miyagi. Just as with the Karate Kid, the dog can’t get the big picture until it has the movements necessary to actually do the behavior. (We take for granted that because a dog can lie down on its own that it knows how to lie down our way. That is a mistaken assumption.)

To become a good dog trainer you must understand that even if the dog’s tail is wagging and it continues to work for you, the frustration level of attempting something new will remain until the behavior is fluent. You will also understand why errors in the early part of training exist because the dog isn’t fluent – just like your attempt to write in cursive curls and swirls with your “off” hand. The solution is to grit your teeth and just do it. The same is true for your dog but as they can never understand the reason for any of the things you teach, this exercise will teach you the two most critical attributes of a good trainer – patience and empathy for the student.

Interesting exercise Gary.

In your personal opinion, what do trainers lack more these days; patience or empathy?

Brandon, they assume that intellectual activity translates into expertise. Some things you can only learn with Wax-On, Wax-Off experience. Most dog trainers won’t do anything that is outside their experience – behavior analysts and “scientific trainers” are included in that. If I say “do this 100 times” and then we’ll talk about it, most people would balk that they need to do it 100 times. Unfortunately, some things can only be learned once your brain knows “normal” so well that the tiniest deviation can be recognized. I would make that a general statement – precise discrimination requires a wealth of data for comparison and a gradient scale that matches the deviation. A yard-stick can’t do the work of a micrometer.

That was a great exercise. Thanks, you kick started my brain again. I have run into the same thing with clients. They insist that their dog ‘knows’ something but just won’t do it. I ask, “if he knows it why isn’t he be doing it?” I have the hardest time getting the owners of fearful dogs to realize that they need even more repetitions before the dog gets comfortable enough with the new behavior to be able to repeat it in any situation. I tell them that they have to realize that the dog’s brain is kind of like Swiss cheese when he’s in a fearful state and it takes longer for learning to take place. I’m trying to figure out a way to use this exercise to help them understand. I have tried speaking Greek to them and asking how long it would take them to figure out what I wanted. Sometimes that helps but I am open to any other suggestions.