It is easy to get comfortable with specific practices and expectations. The more we refine our methods the more likely we are to unintentionally offer a cookie-cutter approach – because of our past successes. Those accomplishments positively reinforce specific courses of action that generally lead to beneficial outcomes. However, our choice of tools may be the result of something else…our own comfort. In the majority of cases that isn’t a problem. When a dog doesn’t fit the mold, doing what comes naturally may not be the best solution. The biggest casualty of such complaisance is the dog sitting right in front of us. If we fail to examine a dog’s needs as an individual we may well go astray and give them, not what they need, but what we choose to give them.

Limitations, practical and ideological:

There are two main reasons trainers tend to ignore the dog in front of them. One is practical. The other is ideological. If you are wedded to specific tools it shapes your thinking. Meaning if you tell me someone’s tools I’ll tell you what they can’t or won’t do. It’s not because they aren’t skilled it’s because they intentionally put limitations on their imagination. For instance, if you assume that excessive barking can only be fixed with some kind of “bark collar” you are likely going to be frustrated when the collar doesn’t stop the dog from barking. You will also be likely to assume that if the first collar doesn’t work that some similar solution is the only one available. Hey, here’s a thought. The dog just told you your method isn’t working like it normally does. Why would you do more of something that didn’t work? Why assume that this dog will suppress its barking just like every other dog you’ve worked with?

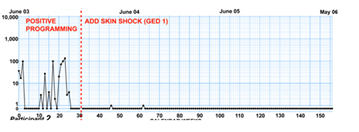

On the flip side, many modern trainers style themselves “all positive” and object to intentionally using any form of punishment. They hold to this ideology based on their belief that there is no behavior that cannot be controlled  by positive means. OK. I’ll bite. Here’s a standard celeration chart of a human with self-injurious OCD. (This is more dramatic than you think. The horizontal lines are logarithmic. The person is attempting to hurt himself as many as 100 times a day) You can see clearly on the left, the part marked “positive programming”, the behavior wiggles dramatically but continues. On the right is after the introduction of contingent skin shock, meaning “try to pound out your eyes and a shock will be delivered”. The behavior goes flat-line. The conclusion is simple. There is at least one behavior that cannot be controlled by positive programming, even under clinical conditions by learned behavior analysts and clinicians. If you think a positive dog trainer has this kind of education and skill you’d be suggesting that they know more than the people who they cite as experts. That’s kind of a no-brainer assumption.

by positive means. OK. I’ll bite. Here’s a standard celeration chart of a human with self-injurious OCD. (This is more dramatic than you think. The horizontal lines are logarithmic. The person is attempting to hurt himself as many as 100 times a day) You can see clearly on the left, the part marked “positive programming”, the behavior wiggles dramatically but continues. On the right is after the introduction of contingent skin shock, meaning “try to pound out your eyes and a shock will be delivered”. The behavior goes flat-line. The conclusion is simple. There is at least one behavior that cannot be controlled by positive programming, even under clinical conditions by learned behavior analysts and clinicians. If you think a positive dog trainer has this kind of education and skill you’d be suggesting that they know more than the people who they cite as experts. That’s kind of a no-brainer assumption.

In my earlier example it points out that sometimes a dog comes along that requires a virtual 180 degree change in your thinking. If we stick to the example of barking that is actually a great platform to test the conclusion. What if we click a clicker and give the dog a treat for every single bark? That is about as close to opposite a bark collar as you can get. Forget your first-impulse assumption that you will be rewarding the bark. Now tell me what actually happens rather than what you assume. I know because I’ve done it many times. The barking decreases. In most cases it drops by 90%. Controlling 10% of the barking is far easier than trying to confront 100%. That means that if you then use a bark collar the behavior may vanish entirely. The sequence of using both positive and negative made a difference in the outcome. Perhaps the best outcome is less negative, more positive and not arbitrarily trying to stop the behavior by using only one or the other.

Using a target stick to teach a dog to walk

A Practical Consideration: How many times have you actually seen something?

What about a dog that simply won’t budge on a leash. I’m not talking about your garden variety dog that gets tired and simply lies down on a walk or a puppy that doesn’t have any skills walking on leash. I can use a clicker and a target stick to get that dog moving with all positive reinforcement. But what if the dog has a history that makes any attempt to move it a train-wreck. This is a regular occurrence in the humane and animal control industries. It is not a regular event in dog training. While a dog catcher might deal with this several times on one day a trainer might see this once is a blue moon. If you are interested, the solution is to put tension on the leash and pull the dog forward enough to make it take a step. Repeat. Over a series of these “bumps” the dog figures out that the way to postpone (and then eliminate) the pull is to take more steps. In most cases you can get a dog walking in about a minute. I’ve done that literally hundreds of times when I was a shelter manager and animal control officer. It wasn’t my “go-to” solution but it was something I had in my back pocket whenever it looked like a good way to go. I had used this method for many years. Meaning I always had a broad set of solutions for this problem that had worked in every case. Then I met Charlie.

Charlie was a medium-to-large, shaggy, mess. He was originally owned by a hoarder, rescued, kept in rescue for a couple years, put in another rescue, held at a vet clinic for a couple months and then adopted by one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. The dog had literally never been on a leash in his life. His only connection with a human being had been by a “rabies pole” AKA ‘Control Stick”. I didn’t know that at first. I figured this would be another open and shut case with some deft leash handling for a couple of minutes and an insistent, intermittent tension on the leash. My shelter and animal control experience told me that was the logical first step in getting Charlie comfortable with his new life. I have handled hundreds to a couple of thousand dogs that didn’t want to walk or didn’t like people. That experience tells me what is likely to help and also what might cause damage. As those tools and methods are still used every day in every shelter in the country I know that thousands of dogs are handled in that fashion with no adverse long-term effects. If you have never used one you cannot possibly know the “top end” of when it’s moving toward potential harm. Also, if you’ve never even seen a dog flip-out on a control stick you will be shocked by the violence and your judgment will be impaired. If you doubt this, start volunteering at the shelter nearest you and stick around long enough to see it in action.

So I used my very broad tool box and none of it worked. Charlie fought the whole process, violently. First, we had nothing he really wanted other than to be left alone. He wouldn’t take treats in the presence of any human. He would tolerate touching but didn’t want it or like it. Touching him simply caused him to do nothing. He would sit there and let you touch him. That’s it. There can be no use of positive reinforcement if you have nothing the dog will work to get. It was like making a child sit in a dental chair while the dentist runs the drill at high speed and whirls it around the kid’s face. Second, if you tried to put a leash on him he would let out a low, soft, oh-so-dangerous growl. That is a very serious threat. Noisy dogs aren’t the problem. It’s the quiet ones that you have to really watch. Additionally, it was very difficult to read his intentions. He was a very long coated dog and you couldn’t see his eyes. The most difficult type of dog to read is one that doesn’t give any outward signals to tip you off on their intentions. That is why most dog people are cautious of dogs like Shar Peis, Chow Chows and Pit Bulls. They don’t give signs before they launch. The better you are at reading dogs the more uncomfortable it is to have an ‘unreadable’ dog in front of you.

So we worked on getting the hair off his eyes. That took two sessions. We had to get an ages-old collar off him – which was very dicey as he threatened us any time we tried to handle his head. I had to put leash pressure on him through a chain-link fence during the procedures. When I finally got a leash on him, a process that took incredible caution and skill, he bit through it so violently that he bloodied his mouth and sliced it in two. So I put a very long choke-chain on him and padded the chain with a tubular, rubber chew toy. It was very long because I had to make a big loop to get it over his head using a fake hand on a three-foot PVC pipe. The fake hand worked beautifully to hold the loop open and then release it. It also took about 20 tries as he would move his head out of the way at the last second. With the choke chain padded with thick rubber, he could bite it but not cut through it and his mouth would be protected while I got him moving…or so I thought. Charlie wasn’t having any of it. He bloodied his mouth somehow but wouldn’t walk more than a few steps before doing an alligator roll. The maddening thing was that he actually would do a burst of about five or six feet and then go back to fighting it.

To his credit he never tried to bite me. (Although all the threats were there.) He never lunged. He had the longest fuse in the world – but he wasn’t going to walk on a leash. That’s when I knew that he had never been moved with anything other than a control stick. His immediate reaction of biting ferociously and chewing at anything around his neck is something I’ve seen many times – with dogs on a control stick. If you ever see one up close you’ll notice the gashes in the vinyl at the end of the stick. Most of them have dried blood and gashes on them from the many dogs that bit it violently. The bite is reflexive so the dog doesn’t stop biting even though it doesn’t get them off the hook. That was an eye-opener and it made perfect sense. There wasn’t any way this dog was taken from a hoarder and moved from place to place without that kind of control. His life at the vet clinic started drugged and unconscious so they could neuter him. Even if someone, somehow, had walked him successfully at some point, he had reverted to using violence to get people to leave him alone.

Most of them have dried blood and gashes on them from the many dogs that bit it violently. The bite is reflexive so the dog doesn’t stop biting even though it doesn’t get them off the hook. That was an eye-opener and it made perfect sense. There wasn’t any way this dog was taken from a hoarder and moved from place to place without that kind of control. His life at the vet clinic started drugged and unconscious so they could neuter him. Even if someone, somehow, had walked him successfully at some point, he had reverted to using violence to get people to leave him alone.

Equally maddening was that he would show flashes of improvement and then put one more speed-bump in the way. We would fix one problem and then get hit with another. I pushed as far as I have ever pushed a dog in training because I knew that if I could get him walking it would nudge him through a veil and we would get grand success. After about eight sessions we stopped the process. It wasn’t working and I wasn’t willing to continue the constant, violent struggle. Not because it was unpleasant, though it certainly was. I have rescued many dogs from the street who didn’t want to go with me. Humane ethics do not allow you to walk away from that kind of problem because it might upset the animal to drag it out of a drain pipe that is filling with water and will soon drown the dog. (Yes, I’ve done that, too) I long ago learned that the dog’s life has to be considered in its entirety when you decide on what is appropriate to fix a problem – just like a veterinarian. If cutting a dog open and thereby creating weeks of pain and a potential serious abdominal infection will save a life, a vet is obligated to do it. Fixing a dog’s behavior relies on the same ethics. The reason we stopped was because it simply wasn’t working well enough to assume that more of the same would be the cure.

The owner and I decided to let him simply live in his 20’X10′ pen for awhile. The owner could already sit and touch him quietly. We knew that because we had successfully trimmed his facial hair. (With a lead on his neck fed through a chain-link fence so he couldn’t lunge forward and bite. Meaning with a huge layer of safety between his teeth and his owner.) That ultimately was the solution. After about four months of very slow, very gentle contact with a single human-being he changed. There was no way in advance to predict that. There was every opportunity to fix him rapidly through methods that are used in humane societies every day of the week – in secret. (If you wish to question whether or not my attempt to rapidly fix Charlie was humane, call your local shelter manager and complain closer to home. They handle fractious dogs with no thought to fixing them. They just manage them and kill them. ) There was a risk factor in doing nothing. If he escaped from his pen he was on the edge of the Sonoran Desert. Once away there wasn’t any possibility of catching him. I didn’t worry too much about putting pressure on him because of his rough handling being “rescued” from the hoarder. If it was going to ruin his psyche it would have already happened. Additionally, I know the safety limits and have never exceeded them. My job is to get the dog into a new life as quickly as possible. That requires knowing when to switch horses in the middle of the stream. That means you have more than one horse. About 98% of what I do is with positive reinforcement. When you have a dog that isn’t going to let you use that part of the spectrum you better have that other horse saddled.

This is a very interesting article. I agree that it is vital that we give our dogs what they really need. For example, dogs need to be walked on a regular basis. This is how they get an adequate amount of exercise.

nice