When I decided to offer behavior services I had already trained two dogs as urban animal control dogs. If you are interested in that story, go to my blog and put ‘Megan’ in the top search box. My dogs were as good in the field as the city’s police K9’s and in some ways better. However, I have a great deal of respect for kn owledge and learning and decided to delve into the world of science. I called the University of Washington bookstore to see if they had Conditioned Reflexes by Pavlov. (The correct translation of the original Russian title is ‘Conditional Reflexes’. That will make a difference in this conversation, later. )

owledge and learning and decided to delve into the world of science. I called the University of Washington bookstore to see if they had Conditioned Reflexes by Pavlov. (The correct translation of the original Russian title is ‘Conditional Reflexes’. That will make a difference in this conversation, later. )

It took about a year and a half to digest the book. I took notes. I didn’t go to the next experiment until I understood the charts, graphs and data necessary to know the material. That’s because I wasn’t doing it for a grade on a test, I was doing it to crack open the oyster and find the pearls.

So, here’s a pearl for you – maybe two.

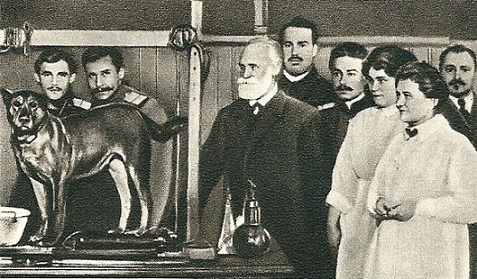

Prior to Pavlov, no one had studied behavior with the diligence of a real scientist. He decided to study the topic of how animals make associations. Like any great scientist, he never deviated from connecting his work to nature. For instance, he opens the book with this statement.

“It is pretty evident that under natural conditions the normal animal must respond not only to stimuli which themselves bring immediate wavers of sound, light and the like – which in themselves only signal the approach of these stimuli; though it is not the sight and sound of the beast of prey which is in itself harmful to the smaller animal, but it’s teeth and claws. ”

This is a monumental thought. It explains the reality and necessity for animals to make associations between seemingly unrelated or unknown things. A bear looks like a big, fat, cuddly, waddling silhouette. How cute. The wolf has to somehow 1) Remark on this new thing 2) Innately question it’s nature as a threat or a help. 3) React in advance of any contact. We know they can do that because they still exist. If they couldn’t, they would have died out long ago.

This is where it gets interesting. Pavlov created experiments to model this natural process. He didn’t need to know IF it worked, he wanted to know WHEN it worked and WHEN it didn’t. So, he called the book “Conditional” Reflexes. His work is drenched with the assumption that this type of learning does not always work and he wanted to find out the details.

Here’s where American psychologists went South. The English translation was called Conditioned Reflexes – which describes a done-deal. It does not suggest limitations. They didn’t read the work with any thought to how it actually works or when it doesn’t. Then they merrily started making rules and stealing terms to suit their own purposes. That was a mistake. Here’s a pretty important one…

Pavlov’s most basic experiment took the sound of a bell (something that does not occur in nature and avoided the possibility of an instinctive sensitivity) and followed it with food. He said it took him between 20-50 repetitions MINIMUM to make a 100% association. That meant the if you rang the bell the dog would give 100% of the reaction triggered by real food.

Before I get to the punch line, I have to mention one other thing. I said the food ‘followed’ the bell. The ‘followed’ was an important factor. Pavlov tested the sequence very early on. He took a dog and gave it food and THEN rang the bell. After 400 repetitions, the dog made no association to the bell. He reversed the sequence and within about 20 repetitions the dog had a perfect association between the bell and food.

So, here is the incredibly stupid conclusion that people got from this work. They forgot that he wasn’t really studying how to create a 100% replacement signal for a reflexive reaction. They thought, incorrectly, that the bell could act as a surrogate for the food. Go back and think about his statement above. Yes, it’s the sight of the bear that precedes being killed by the claws – but the sight of the bear absent any real threat becomes rapidly neutral. If you ring the bell and stop feeding the dog, the association is weakened. The purpose of the bell isn’t to replace the food.

Now I will tell you how this is almost universally misunderstood with a single quote…

“I didn’t have to actually bonk the dog, I just said “NO” and showed him the bonker.”

The purpose of the word “NO” is to identify a behavior via “wavers of sound, light and the like”. It is not to eliminate the actual consequence that insures a change in behavior. Attempting to do away with tangible rewards and punishment is doomed to failure as the association becomes “conditional’.

Insightful and thought-provoking as always. I read your posts because you challenge the status quo at both ends of the spectrum and make me think and that’s a good thing. 🙂