|

|||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

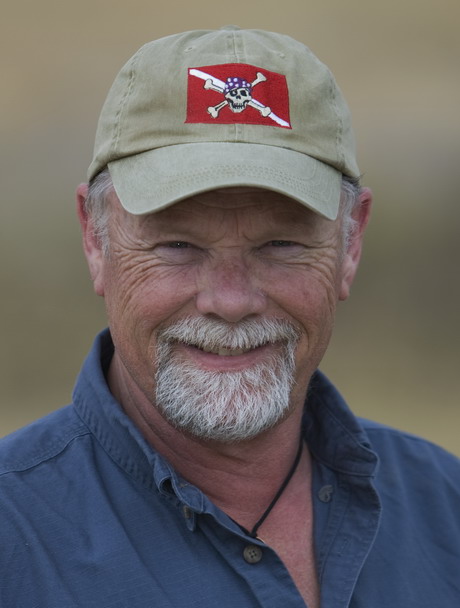

An Introduction to Aggression for Veterinary Staff, Groomers and Handlers By Gary Wilkes ag·gres·sion 1. The act of initiating hostilities or invasion. 2. The practice or habit of launching attacks. 3. Hostile or destructive behavior or actions 4. The practice or habit of using teeth and claws to damage and/or terrify veterinary personnel, groomers and trainers.

When I started to write this handout, I decided to prioritize the topic in the context of veterinary care, grooming and pet ownership. Here’s what I came up with. 1) Claws can be nasty, teeth can be deadly 2) Cats can be nasty, dogs can be lethal. Using this logic, we will place the greatest importance on dog bites, followed by cat bites and scratches. The Five Types of Aggression: It is very trendy in modern behavior and training circles to define many different types of aggression. The idea is to classify aggression into sub-types to give you insight about their nature and cure. Some of the sub-groups are: dominance aggression, territorial aggression, food aggression, redirected (sometimes called misdirected) aggression, fear aggression, possessive aggression, predatory aggression and pain aggression. In the majority of cases, detailed classification of aggression is something you do after the fact to aid in treatment. In the world of veterinary care and grooming I think there are only five major types. These are rarely listed in dog training and behavior circles, but I think you will recognize them. That hurts, I am going to bite you, now. This is the easiest form of aggression to anticipate. You know which procedures cause pain and discomfort. If you can anticipate when the painful part starts, you can make your grip a little firmer, just before the dog goes ballistic. If the dog accepts the pain and doesn’t resist, make sure you soften your grip! If you do not relax the pressure when the animal relaxes, you run the risk of triggering a constant struggle. All good handling requires that any restraint be held only so long as the animal struggles. Once the struggling ends, the tight grip must end. (If the animal simply goes ballistic, this does not apply. In that case, you have to simply hold on for dear life and get the job done.) That hurt the last time I was here, I am going to bite you before you can do it again. If the dog has prior experience he may decide to initiate a bite well in advance of any actual handling. This process may start when the dog comes into the reception room. By the time the dog is in the exam room or on the grooming table, it may be ready to bite anyone who tries to touch or handle it. Someone else hurt me once, so I will bite you, now. This is a pretty self explanatory category. Vets wear white coats, techs and groomers wear scrubs or smocks. If a kennel worker is wearing scrubs and the dog thinks scrubs mean “vet tech” the dog may bite the wrong person – and any other combination of this concept. Sometimes kennel workers set the stage for a reverse association. Be aware that your appearance can trigger a bite, even if you have never had bad relations with a particular animal. I generally bite people, I don’t need a reason. Some animals have such a long and broad history of violence that they may bite at any given moment – even after typical provocation has failed to trigger a bite. This type of dog may allow you to remove stitches, palpate a sore belly, trim its nails or get a fecal sample – and bite you on the way out of the exam room. I’m a Chow Chow (Or fill in the blank with any breed you don’t trust) A veterinary neurologist friend of mine once corrected me for saying I was working with a vicious Lhasa. “Why bother saying vicious? It’s a Lhasa.” Every breed of dog has a published breed profile that claims “friendly with kids, good with old people, loyal, devoted, sweet, wonderful, special, easy to train.” Don’t believe it. Some breeds should be considered dangerous until proven otherwise. You can usually prove they are safe after the owner picks up the ashes, post cremation. I won’t bother to list the generally aggressive breeds – you know which ones they are.

General rules for avoiding a bite:

Before we try to predict when a bite is likely to occur, I would like to review some of the things I do to keep myself safe.

Never make direct eye-contact with a dog you haven’t slept with. Use your peripheral vision to watch what the dog is doing. If this seems odd, just remember that all dogs perceive eye-contact as a threat. Just because a majority of dogs don’t overtly react to direct eye-contact doesn’t mean they think it’s a friendly gesture. Once you start adding the five types of aggression to the mix, eye-contact can be the trigger for a bite, even though you made eye-contact previously. Try to always avoid bending over a dog from the front. Never “pat the nice doggie on the head.” Towering over a dog is normally considered threatening. Dogs consider their head, neck and shoulders to be private areas – about as private as we consider our groin. When you approach them from the front and above, it’s like someone you don’t know goosing you. Just like people, some dogs like that and some dogs don’t. When you pick up a dog lamb-style, (from the side, placing one arm dog’s chest and the other around the rump.) you’re a bit less of a threat than standing right over the top, but this may also be seen as a threat. Since this type of lift is common to your job, a safer way to do it is to squat down to wrap your arms around the critter’s legs -- then lift the dog using your legs, rather than your back. Sorry, but OSHA actually has this one right. Unless you want chronic back trouble, never lift anything with your back, even a dog. If you are going to make a first contact with a dog, place your hand below the dog’s chin – never above the head. Try to gently touch the dog’s chest before you go roaming around the ears, lips and muzzle. If you have to handle a dog’s leg, start high, near the elbow, and work your way down without appearing to pull it forward. Pulling forward with the wrong dog usually causes the dog to pull his leg back, arch his neck and bite your hand. Did I mention that dogs have reaction time about 1.5 times faster than the fastest humans? Once you have a dog on the table, you can use the weight of your chest to press downward and freeze the dog for a few seconds, if need be. Be careful about this. By pressing your weight forward you are placing your face closer to the biting end of the dog. A good precaution is to get in the habit of having your arm around the dog’s neck so that if you must put “down pressure” on the dog you can have your arm between you and the dog’s teeth. When you are in this posture, you are technically using a wrestler’s “strangle hold.” Your shoulder is touching the dog’s shoulder. Your bicep is touching the dog’s neck and jaw. Your forearm is touching the far side of the dog’s chest and neck. You can either make a fist or turn your palm toward your face and grip the dog’s neck for more security. If you open your hand, you should be looking at your palm. Intelligent use of the lead: In and emergency you can pull the lead in a direction away from the dog’s intended target. You have to think about this in advance and while you are restraining the dog. If someone is assisting and has their face near the dog, pull the lead away from their face. i.e. It’s simple but you must be ready to do that in an instant. Also, learn to make a very quick muzzle by wrapping the lead around the dog’s mouth. This should be done before the dog has a chance to bite you. In general, aggression is an integral part of handling animals. Every time you offer a painful procedure, muzzle or grapple with a dog or cat, you add an entry into the dog’s history. If the dog is easy going, it’s a one-time occurrence and no harm is done. If the dog reacts violently, there is a real possibility of repeat performances that increase the rate and intensity of the violence. Over a sequence of visits, the aggression can pass from simple nuisance to dangerous hazard. Keeping track of a dog’s history is more than just flagging the file. A real history requires looking at the dog’s behavior in the clinic, the salon and at home. Few owners realize that their dog is capable of serious aggression until it is an accomplished fact. If the dog is aggressive during treatment or grooming, the aggression is accepted as unusual, understandable and unconnected with their darling’s real personality. The pain of the treatment will be blamed for the behavior. If the aggression occurs at home, the owner will find other ways to minimize the seriousness of the dog’s behavior. In most cases, the aggression wasn’t aimed at the owners. This allows them to assume that the victim did something that caused the attack. As long as the owner is not the victim, the dog’s behavior may be allowed to escalate through a series of logical evasions and denials. Often they begin to confine the dog when they have company, stop taking the dog for walks and generally avoid the problem at all costs. At the clinic you may be unaware that the dog is gradually becoming a threat. If you aren’t in the reception area you may not see lunging, barking and growling that is now the dog’s normal behavior. Paying attention to the way the owner handles the dog is another aid to keeping you unbitten. Here are some general thoughts to help you play aggression detective.

Death grip on a short leash: Keeping the leash short and holding on for dear life is the sign of a nervous owner. They are afraid to loosen the leash for fear the dog will lunge at a dog, human or cat. Slack hold on a long, taught leash: If the owner is still in a state of denial, they will look everywhere but at their dog. The leash is tight because the dog is lunging at everyone. This person attempts to keep eye-contact with the receptionist and somehow grab and control the dog without looking down. Hesitant hold, tight, erratically tugging leash and very straight posture: This is an owner who is now intimidated by their own dog. They aren’t bending over because they aren’t going to risk putting their face down on that level. They tend to overuse the leash to keep the dog slightly away from them. If it’s a small dog, there is an inordinate amount of tugging to keep the dog away from their legs and feet. If they are sitting, the dog will not be in their lap. They will hand the leash to you tight and vertical, often lifting their arm high in the air to keep tension on the leash. The topic of aggression in a clinic or salon context is so broad that no single presentation or handout can cover it. As with many dynamic processes, aggression is a subject that requires experience, observation and analysis to fully understand. Because of the nature of your job, you routinely take animals to the end of their patience and the beginning of self defense. Watching the most skilled handlers at your clinic or salon and practicing your own handling skills are two ways to be safer and more effective with aggressive animals. Oops. I almost forgot cats. OK. Aggressive cats. Use a heavy towel to cover the cat’s body. Put “down pressure” on the cat with your hands. Attempt to gain access to the cat’s head by rummaging around (oh, so carefully) under the towel. Line up the knuckles of one hand with the cat’s spine, thumb pointing toward the biting end of the cat. If the cat is pointing to your right, you’ll use your left hand to grip the head and vise versa. Grip the cat’s scruff with four fingers – this is like the movement you use to squeeze the hand brake on a bicycle. The important thing is to only use your fingers to grip the scruff – your thumb needs to remain free. Once you have the scruff gripped, lay your thumb along the cat’s cheek bone and keep it there, no matter what happens. Put enough pressure on the skull so that the cat is looking slightly away from you. This prevents the cat from turning its head toward your hand and biting you in the wrist.

If you must pick the cat up after you have gripped its scruff, try this. Holding the cat by the scruff as described above, lift the cat’s torso by rotating your wrist back from the cat’s head. Grab the cat’s feet and hold them together with your other hand. As you lift the cat the rest of the way off the table/floor, stretch the cat with both arms to its full length, while continuing to arch the cat’s back. If anything goes wrong, take the cat quickly to the ground and continue your “down pressure.” Call for help and a bigger towel. Pass the cat to the person who came to your assistance. Tell the person to hold the cat for a second. If the person complies with your request, you have a slim window of opportunity to escape. (That’s a joke, in case you missed it.) If all this sounds incomprehensible, don’t worry too much. Get a very docile cat and have someone read the instructions while you try to follow them. If you still have trouble, call or email me. |

|||||

|

Copyright 1994-2015 Gary Wilkes. All rights reserved.

|

|||||